2 Persistence and Change

You would presumably not be moved by the purported puzzle below:

- I’m found in a certain spatial region \(R\).

- I’m found in a spatial region \(S\) which is disjoint from \(R\).

- Therefore, one and the same object is found in two disjoint spatial regions.

For there is a completely unproblematic gloss of these facts:

- One of my parts is found in a certain spatial region \(R\).

- One of my parts is found in a spatial region \(S\) which is disjoint from \(R\).

- Therefore, one and the same object has parts found in two disjoint spatial regions.

Indeed, to be spatially extended is to have parts found in disjoint regions.

But temporal extension appeas to be different:

- I have been found in the twentieth century.

- I have been found in the twenty first century.

- I have been found in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

And, on the face of it, we may add:

- All of me has been found in the twentieth century.

- All of me has been found in the twenty first century.

- All of me has been found in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

That would appear to suggest a difference between persistence and spatial extension.

To persist is to be found or to be present at more than one time; to exist over time; to survive from one time to another, etc.

To be found or present at one time is not to be entirely found or entirely present at that time … each of you is found at the present time despite the fact that you are not entirely inside that temporal moment.

To be found at one time, to exist at one time, to be present at one time will all eventually be analyzed in terms of a primitive locative relation.

The key thought is that to persist is to be present throughout an extended temporal interval, which means that one is not confined to a single instant. To be confined again will require further analysis in terms of a primitive locative relation.

2.1 Perdurance and Endurance

A first pass at the distinction is due to David Lewis:

To endure is to be wholly present at more than one time within a certain interval.

To perdure is to be partly present at each moment of an interval and to be wholly present at only at the whole interval

Here is David Lewis in (Lewis 1986):

Let us say that something persists iff, somehow or other, it exists at various times; this is the neutral word. Something perdures iff it persists by having different temporal parts, or stages, at different times, though no one part of it is wholly present at more than one time; whereas it endures iff it persists by being wholly present at more than one time.

Perdurance is modeled after spatial extension. To be spatially extended is to be partly present at each point of a spatial region, and to be wholly present at the whole region. The thought is that temporal extension is akin to spatial extension.

2.1.1 Perdurance

To perdure is to be partly present at multiple times.

Events appear to perdure. They have temporal extent and temporal parts of the event occupy briefer time periods, e.g., this course is part of a summer school and it consists of three temporally extended lectures over the course of a week.

Temporal parts are segments or stages of a material object along a temporal dimension. Consider the spatiotemporal region I occupy in the four-dimensional manifold. Now, consider a spatiotemporal region, which shares exactly the same spatial boundaries but has a more limited temporal extent, e.g., from 2000 to 2010. A temporal part of mine would be a material object, which would exactly occupy that spatiotemporal region.

To use Ted Sider’s illustration in (Sider 2003), consider your own life:

Think of your life as a long story. … Like all stories, this story has parts. We can distinguish the part of the story concerning childhood from the part concerning adulthood. Given enough details, there will be parts concerning individual days, minutes, or even instants.

According to the ‘four-dimensional’ conception of persons (and all other objects that persist over time), persons are a lot like their stories. Just as my story has a part for my childhood, so I have a part consisting just of my childhood. Just as my story has a part describing just this instant, so I have a part that is me-at-this-very-instant.

You, for the four-dimensionalist, are nothing but an aggregrate of person stages. Here is an illustration of perdurance from (Gilmore, Calosi, and Costa 2024):

There is a qualification. The illustration simply presupposes that time intervals are composed of time instants, and that no matter what some instantaneous temporal parts may be, they themselves compose another temporal part. But one may be a perdurantist and leave open whether there are time instants.

2.1.2 Endurance

To endure is to be wholly present at multiple times.

I have been wholly present in the twentieth century.

I have been wholly present in the twenty first century.

I have been wholly present in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

But what exactly is for me to be wholly present somewhere? One may be tempted to give the following gloss:

All of my parts have been found in the twentieth century.

All of my parts have been found in the twenty first century.

All of my parts have been found in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

Ted Sider objects to this gloss in (Sider 2003) on the grounds that material objects often change their parts. Since I have often gained new parts over the years, it is not true that all of my parts could be found back in the twentieth century. So, it is false that I have been wholly present in the twentieth century, since some of the newer parts have not be found there.

Or consider my car, which, we may suppose, has lost a mirror over the course of the years. Is the mirror part of the car? If it is, notice that while the mirror is not present now, the car appears to be. So, it is now wholly present now.

Sider briefly considers a reply on behalf of the endurantist. Maybe the relation of part to whole should itself taken to be relative to a time in which case would rephrase the statements as follows:

All of my parts in the twentieth century have been found in the twentieth century.

All of my parts in the twenty first century have been found in the twenty first century.

All of my parts in each century have been found in each century, even though the two centuries are disjoint temporal intervals.

True, but unremarkable. Even the perdurantist would agree to that gloss.

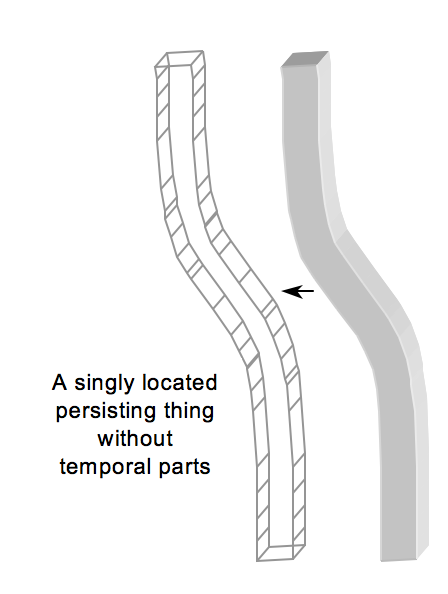

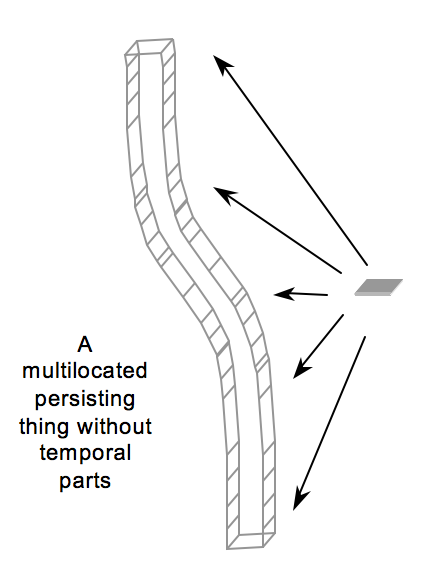

More recently, (Parsons 2007) has proposed another model for endurantism. To endure, for Parsons, is to be a temporally extended simple: to the extent to which I’m a temporally extended object without temporal parts, I’m wholly present now; all of my temporal parts are present now.

Consider the case of spatial location. To say that I’m wholly present in the room is presumably to say that all of my spatial parts are in the room. That would not be the case, for example, if I step over the threshold or stick my head out of the door. It may seem that to be wholly present in the room is much like to be entirely within the room, but there are exotic counterexamples to the identification. Consider the case depicted by Figure 5a in (Gilmore, Calosi, and Costa 2024):

The object \(o_1\) in the diagram is an extended simple, which is wholly present in both \(r_1\) and \(r_2\). It is wholly present in \(r_1\) because all of its spatial parts are present at \(r_1\), and likewise for \(r_2\). That is:

- All spatial parts of \(o_1\) are present in \(r_1\)

- All spatial parts of \(o_1\) are present in \(r_2\)

It is, however, not entirely within either \(r_1\) or \(r_2\). So, if there are extended simples, then no spatial part of them fails to be found at a region at which they are found. So, they are wholly present at every region at which they can be found.

Temporal location is not the same as spatial —or even spatiotemporal— location. If someone has been born at the same time instant as another person have and comes to die at exactly the same time as that person, then they will have exactly the same temporal location even if we differ with respect to spatial location.

Let us return now to the case of temporal location. One may now gloss wholly present at a time or time interval similarly. To be wholly present now is for all temporal parts to be found now.

When we deploy the gloss to the case with which we started, we find:

All of my temporal parts have been found in the twentieth century.

All of my temporal parts have been found in the twenty first century.

All of my temporal parts have been found in two centuries, which are disjoint temporal intervals.

To say that my car is wholly present now is just to say that all of its temporal parts are present now, but notice that the mirror that used to be part of my car is not —and had never a claim to be— a temporal part of my car.

Here is an illustration of the present model of endurance drawn from (Gilmore, Calosi, and Costa 2024):

There is an alternative model of endurance in the literature, one on which persistence is regarded as akin to travel through time. To travel through time is to occupy different moments in time in its temporal entirety. This is parallel to a view of travel through space in terms of the occupation of different places in space in its spatial entirety. Unfortunately, the analogy breaks down, since travel through space presupposes time as a dimension of variation. There is no similar dimension of variation one may appeal to in order to make sense of travel through time.

We will revisit the difficulty later once we develop a framework to regiment talk of temporal location. In the meantime, the picture that emerges is one of a three-dimensional object in a certain locative relation to different time instants. The illustration below appears in (Gilmore, Calosi, and Costa 2024).

We postpone the question of how to articulate the locational model of endurance until next time. In the meantime, however, we look at the interaction between the models of persistence and the problem of change.

2.2 The Problem of Change

Consider the case of a candle as described by Sally Haslanger in (Haslanger 2003):

Suppose I put a new 7-inch taper on the table before dinner and light it. At the end of dinner when I blow it out, it is only 5 inches long. We know that a single object cannot have incompatible properties, and being 7 inches long and being 5 inches long are incompatible. So instead of there being one candle that was on the table before dinner and also after, there must be two distinct candles: the 7-inch taper and the 5-inch taper. But of course the candle didn’t shrink instantaneously from 7 inches long to 5 inches long: during the soup course it was 6.5 inches long; during the main course it was 6 inches long; during dessert it was 5.5 inches long. Following the thought that no object can have incompatible lengths, we must conclude, it seems, that during dinner there were several (actually many more than just several) candles on the table in succession.

There is one candle on the table throughout the duration of the dinner.

One and the same candle has changed in length from one time before the dinner to another after dinner.

But the lengths are incompatible with one another, since nothing is both 7-inches long and 5-inches long.

Haslanger uncovers four presuppositions involved in the puzzle:

| Persistence | One and the same object persists through change. |

| Incompatibility | Change involves incompatible qualities. |

| Non-Contradiction | Nothing exemplifies incompatible qualities. |

| Proper Subject | The proper subject of the attribution of incompatible qualities is the object to which the change applies. |

Different models of persistence suggest different responses to the problem of change.

2.2.1 Perdurantist Change

Perdurantists deny the Proper Subject condition. The candle is a four-dimensional object, and it is not 5-inches or 7-inches long. It is only instantaneous temporal parts of the candle that exemplify the incompatible qualities.

From the perspective of a perdurantist, change is akin to spatial variation:

The candle varies in color from place to place because different spatial parts of the candle exemplify different colors.

The candle varies in length from time to time because different temporal parts of the candle exemplify different lengths.

Here is (Sider 2003), p. 2:

A person’s journey through time is like a road’s journey through space. The dimension along which a road travels is like time; a perpendicular axis across the road is like space. Parts cut the long way – lanes – are like spatial parts, whereas parts cut crosswise are like temporal parts. US Route 1 extends from Maine to Florida by having subsections in the various regions along its path. The bit located in Philadelphia is a mere part of the road, just as it is only a mere part of me that is contained in 1998.

A road changes from one place to another by having dissimilar sub-sections. Route 1 changes from bumpy to smooth by having distinct bumpy and smooth subsections. On the four-dimensional picture, change over time is analogous: I change from sitting to standing by having a temporal part that sits and a later temporal part that stands.

2.2.2 Endurantist Change

This is not open to those endurantists for whom the candle is a temporally extended simple. They deny, for example, that the candle has momentary temporal parts with different lengths.

Endurantists tend to deny the Incompatibility condition. There is, however, more than one way in which the relevant qualities may be made to be compatible:

The A-theoretic approach takes tense seriously. The relevant attributions are tensed. Compare with McTaggart’s original puzzle. The A-theorist takes sense seriously in order to accommodate change from future to present to past. That is, we should distinguish between the fact that a moment of time will be present and the fact that it is now present, and the fact that it has been present. Likewise, for the A-theorist, we should distinguish between the fact that the candle will be 5-inches long, the fact that the candle is now 6-inches long, and finally, the fact that the candle has been 7-inches long. There is no incompatibility between those lengths provided their attribution is properly understood.

The B-theoretic approach construes the qualities as relations to times. That is, you may be an endurantist even if you subscribe to the B-theoretic picture of time as a static fourth dimension of variation. You may now draw a distinction between the fact that the candle is 5-inches long at one time, and it is 7-inches long at another time.

David Lewis claims that the B-theoretic approach rests on a mistake in (Lewis 1986):

[Maybe] shapes are not genuine intrinsic properties. They are disguised relations, which an enduring thing may bear to times. One and the same enduring thing may bear the bent-shape relation to some times, and the straight-shape relation to others. In itself, considered apart from its relations to other things, it has no shape at all. And likewise for all other seeming temporary intrinsics… The solution to the problem of temporary intrinsics is that there aren’t any temporary intrinsics. This is simply incredible, if we are speaking of the persistence of ordinary things.… If we know what shape is, we know that it is a property, not a relation.

A quality is temporary if and only if it is had at some times but not others, e.g., being a student, being married, being bent, etc.

A quality is intrinsic if and only if it is had by a material object merely in virtue of the way the object is and not in virtue of the fact that it stands in certain relations to other objects, e.g., being round, being bent, etc. Intrinsic qualities are shared by duplicates.

There is route from temporary intrinsics to perdurance:

Material objects change from being bent to being straight.

Change from a bent to a straight shape reveals that they are either not temporary intrinsics or not incompatible after all.

If a bent and a straight shape are temporary intrinsics, then they are incompatible.

Either a bent shape is not intrinsic or a bent shape is not temporary.

If a bent shape is not intrinsic, then it is a quality an object instantiates in virtue of of a relation to a time.

A bent shape is not a quality an object instantiates in virtue of a relation to a time.

So, a bent shape is not a temporary quality.

If a bent shape is not a temporary quality, then it must be instantiated by a temporal part of material objects.

So, there are temporal parts.