Chapter 13 Bootstrap in Modelling

In Chapter 11, we introduced the bootstrap, an exceptionally versatile technique. While it is often applied to estimate the standard deviation of a quantity when direct calculation is difficult or impossible, here we encounter it in a very different role: as a tool to enhance model estimation.

Motivation: Most tests related to model building (e.g. testing the significance of parameters) assumes normality and/or large samples. This is not always the case.

For example, in classical simple linear regression: the Gaussian model assumes that the errors are normally distributed. That is:

\[ y_i = \beta_0+\beta x_i +\varepsilon_i\\ \varepsilon_i \overset{iid}{\sim} N(0,\sigma^2) \]

This further implies the distribution of the OLS estimator has the following distribution:

\[ \hat{\beta} = \frac{\sum(y_i-\bar{y})(x_i-\bar{x})}{\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2} \sim N\left(\beta,\frac{\sigma^2}{\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2}\right) \]

And finally,

\[ \frac{\hat{\beta}-\beta}{\widehat{se(\hat{\beta})}} \sim t_{\nu = n-2} \]

where \(\widehat{se(\hat{\beta})}=\sqrt{MSE/\sum(x_i-\bar{x})^2}\)

Inferences about the coefficients \(\beta\) that are based on the T-distribution (e.g. confidence intervals and t-test p-values) will be invalid if the error terms are not normally distributed.

Bootstrap counterparts may be conducted when the data fail to meet these assumptions or data requirement.

13.1 Nonparametric Bootstrap Regression

IDEA: Make no parametric assumptions about the model — resample entire data pairs.

Suppose \(y_i\) is the value of the response for the \(i^{th}\) observation, and \(x_{ij}\) is the value of the \(j^{th}\) predictor for the \(i^{th}\) observation. In this example, \(y_i\)s are assumed to be independent such that:

\[ E(y_i|x_i) = \sum_{j=1}^px_{ij}\beta_j+\beta_0 \]

This means the data is cross-sectional, where rows are independent of each other.

Let’s say that the model being fitted is:

\[ y_i=\sum_{j=1}^p x_{ij}\beta_j+ \beta_0 +\varepsilon_i \]

where \(E(\varepsilon_i)=0\), \(Var(\varepsilon_i)=\sigma^2\), \(cov(\varepsilon_i,\varepsilon_j) = 0\)

Do the following to perform inference on \(\beta_j\) via nonparametric bootstrap:

Nonparametric Bootstrap for Regression Coefficient \(\beta_j\)

Input: Dataset

\((y_1,\textbf{x}^T_1),...,(y_n,\textbf{x}^T_n)\)

Output:

Inference on coefficient \(\beta_j\)

Take a simple random sample of size \(n\) with replacement from the data set.

\[ (y_1,\textbf{x}_1^T)^*,...,(y_n,\textbf{x}_n^T)^* \]

This is your bootstrap resample.

Using OLS (or whatever fitting procedure applies), fit a model, and compute the estimates \(\hat{\beta}_j^*\)

Repeat steps 1 and 2 \(B\) times. (\(B\) must be large)

Collect all \(B\) \(\hat{\beta}_j^*\)s and compute measures that apply.

For POINT estimation

The average of \(\hat{\beta}_j^*\)s is the bootstrap estimate

The estimated standard error is the standard deviation of the \(\hat{\beta}_j^*\)s

Note: the method of averaging the \(\hat{\beta}_j^*\)s is also referred as “Bagging” (See Section 13.3)

For INTERVAL estimation

The simplest approach for constructing a \((1 − \alpha)100\%\) Confidence Interval Estimate is using Percentiles.

\((P_{\alpha/2},P_{1-\alpha/2})\) where \(P_k\) is the \(k^{th}\) quantile.

For interval-based HYPOTHESIS TEST

The usual hypothesis is \(Ho: \beta_j=0\) vs \(Ha:\beta_j\neq0\)

You can use the computed C.I. estimate.

At \(\alpha\) level of significance, reject \(Ho\) when 0 is not in the \((1-\alpha)100\%\) interval estimate.

13.2 Semiparametric Bootstrap Regression

IDEA: Keep the model structure parametric, but resample the residuals nonparametrically.

The following is an algorithm that implements residual bootstrapping

Semiparametric Bootstrapping

Input: Dataset

\((y_1,\textbf{x}^T_1),...,(y_n,\textbf{x}^T_n)\)

Output:

Inference on coefficient \(\beta_j\)

Fit the model using the original data to obtain:

the coefficient estimates \(\hat{\beta}_0,\hat{\beta}_1,...,\hat{\beta}_k\)

the fitted values \(\hat{y}_i=\hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta_1}x_{i1} + \cdots + \hat{\beta_k}x_{ik}\)

the residuals \(e_i=y_i-\hat{y}_i\)

From the residuals \((e_1,...,e_n)\), sample with replacement to obtain bootstrap residuals \((e_1^*,e_2^*,...e_n^*)\).

Using the resampled residuals, create a synthetic response variable \(y_i^*=\hat{y}_i+e_i^*\)

Using the synthetic response variable \(y_i^*\), refit the model to obtain bootstrap estimate of the coefficients \(\hat{\beta}_0^*,\hat{\beta}_1^*,\cdots,\hat{\beta}_k^*\)

Repeat 2,3,4 \(B\) times to obtain \(B\) values of \(\hat{\beta}_0^*,\hat{\beta}_1^*,\cdots,\hat{\beta}_k^*\)

Compute measures that apply (e.g. standard error, confidence intervals, etc…)

Interval Estimation and Hypothesis Test follow the same concept.

13.3 Bagging Algorithm

Bootstrap aggregating (or bagging) is a useful technique to improve the predictive performance of models, e.g., for additive models with high-dimensional predictors.

The idea is to generate several models via bootstrap and aggregate predicted values via averaging.

Bagging is commonly used to improve tree models or decision trees (such method is called random forest)

It is ideal for minimizing the instability or variance of a model in terms of prediction

The following are some examples of application of bagging in regression.

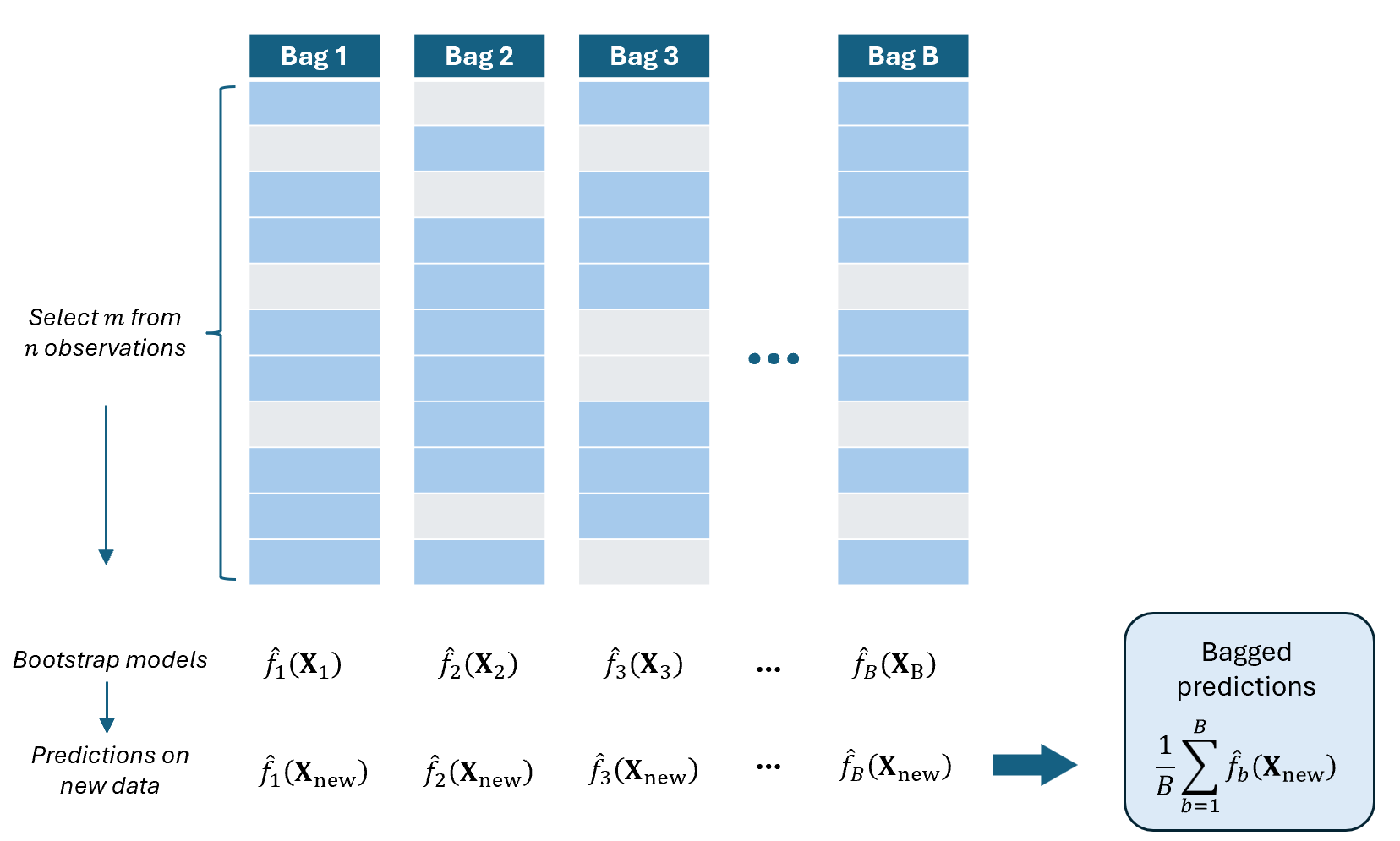

Algorithm: Basic Bagging for Prediction

Inputs:

The training dataset \((\textbf{y},\textbf{X})\) with \(n\) independent observations.

A fitting procedure \(\mathcal{A}(.)\), such as ordinary least squares

Number of bootstrap replications \(B\)

New dataset \(\textbf{X}_{new}\) that we want to get predictions of \(y\) from.

Output:

- The “bagged” predicted value \(\hat{\textbf{y}}_{bag}\) of the new dataset \(\textbf{X}_{new}\)

Step 1: For \(b\) in \(1\) to \(B\):

Draw a bootstrap sample \((\textbf{y}^*_b,\textbf{X}^*_b)\) of size \(n\) with replacement from \((\textbf{y},\textbf{X})\)

Fit a model using the fitting procedure \(\mathcal{A}\) on the bootstrap sample

\[ \hat{f}_b=\mathcal{A}(\textbf{y}^*_b,\textbf{X}^*_b) \]

Compute predicted value on the new data

\[\widehat{\textbf{y}_b}=\hat{f}_b(\textbf{X}_{new})\]

Step 2: Aggregate the predictions

\[\widehat{\textbf{y}}_{bag}=\frac{1}{B}\sum_{b=1}^B\widehat{\textbf{y}_b}\]

Remarks:

The fitting procedure \(\mathcal{A}\) may correspond to any estimator: parametric, nonparametric, linear, or nonlinear.

Each bootstrap sample produces a different model due to resampling variability.

Bagging reduces variance by averaging predictions across models.

For ordinary least squares, gains are most evident when predictors are highly correlated or the sample size is small.

bagging <- function(train, test, formula, model, B){

# formula: y~x

# model: a function that is used to fit a model, such as lm

y.star <- matrix(nrow = nrow(test), ncol = B)

n <- nrow(train)

for(b in 1:B){

index <- sample(1:n, replace = T)

train.star <- train[index,]

mod.star <- model(formula, data = train.star)

y.star[,b] <- predict(mod.star, test)

}

y.bag <- apply(y.star, 1, mean)

return(y.bag)

}You can modify the R code above to accommodate the various extensions of bagging introduced in this book.

Pros and Cons of Bagging

PRO: Bagging induces flexibility in the model

Imagine having a non-linear function formed by aggregating several linear functions with different slopes.

Each base model captures a different linear or local behavior of the data, and their aggregation results in a smooth, flexible function that can approximate complex relationships.

This is advantageous for cases where:

The regression function switches across different regimes or segments (piecewise or overlapping relationships).

The grouping or switching mechanism is hidden or unknown a priori.

CON: The predictive model is hard to interpret.

While bagging improves prediction accuracy, it sacrifices interpretability. Since the final model is an average or majority vote of many base learners, it becomes difficult to trace how each predictor influences the outcome.

Thus, bagging is best suited for applications where:

Prediction accuracy is prioritized over interpretability.

The user is interested in reliable forecasts rather than model explanation.

Examples include financial forecasting, image recognition, and medical diagnostics.

As of now, the basic bagging algorithm is still not that useful.

While bagging can improve predictions for many regression methods, it is particularly useful for “decision trees”, which is not discussed in this course.

Bagging has inspired several useful modifications to its resampling and model-building steps.

Two basic approaches are Random Subsampling and Random Permutations of Predictors.

These techniques are further extended for the computation of Out-of-Bag Errors and Variable Importance Measures.

Random Subsampling

In standard bagging, each bootstrap sample has the same size \(n\) as the original dataset.

Random Subsampling modifies this by taking a smaller sample of size \(m<n\).

That is, instead of resampling \(n\) observations with replacement, we randomly draw \(m\) observations.

Bagging with Random Subsampling

Inputs:

- The training dataset \((\textbf{y},\textbf{X})\)

- Number of bootstrap samples \(B\)

- Subsample size \(m < n\)

- New (unseen) data that contains values of \(\textbf{X}_{new}\) and we want predictions of \(\textbf{y}\).

Outputs:

- The “bagged” predicted value \(\hat{\textbf{y}}_{bag}\) of the new dataset \(\textbf{X}_{new}\)

For \(b=1,2,...,B\):

Draw \(m\) observations from the data (without replacement)

Fit a model \(\hat{f}_b=\mathcal{A}(\textbf{y}^*_b,\textbf{X}_b)\) using the selected \(m\) observations

Use the remaining \(n - m\) observations as the \(b^{th}\) test data

Predict the value of \(\textbf{y}_{new}\) using the new data \(\textbf{X}_{new}\) by plugging in to the fitted model: \(\hat{\textbf{y}}_{b,new}=\hat{f}_b(\textbf{X}_{new})\)

END FOR

COMPUTE “Bagged” predicted value on the new dataset as the average of the predicted values: \(\widehat{\textbf{y}}_{bag}=\frac{1}{B}\sum_{b=1}^B\hat{\textbf{y}}_{b,new}\)

Remarks:

This is almost the same as the basic bootstrap. The only difference is that each bootstrap sample contains only \(m<n\) observations, and elements are obtained without replacement.

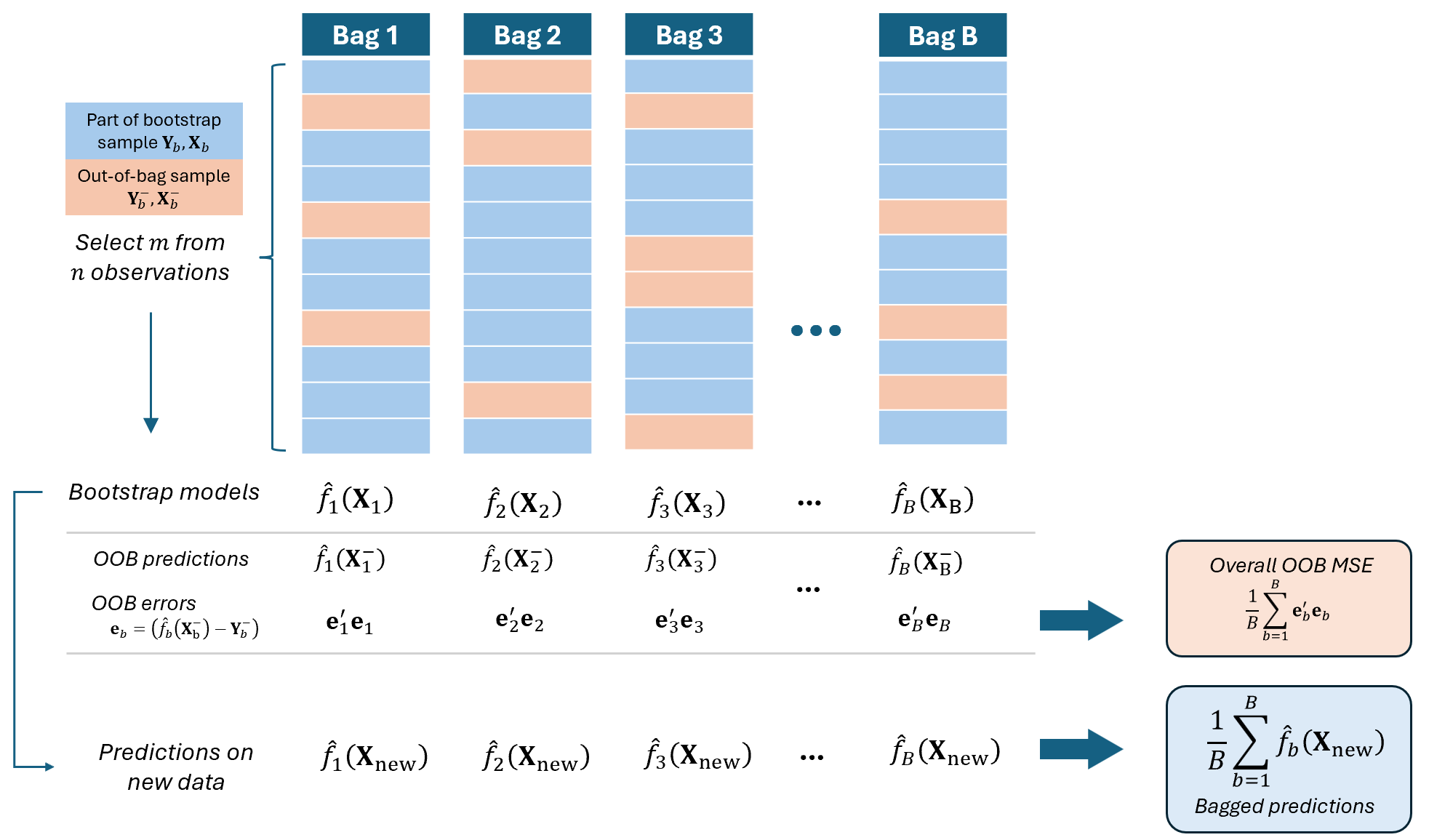

With this approach, we can extend this to obtain “Out-of-Bag Predictions” and estimate “Out-of-Bag Errors” per bootstrap sample.

Out-of-Bag Error Estimation

It turns out that there is a very straightforward way to estimate the test error of a bagged model, without the need to perform cross-validation or the validation set approach.

We can modify the Random Subsampling to enable estimation of the out-of-bag (OOB) error rate for each model:

The remaining \(n-m\) observations not used in training (which we now denote \(\textbf{Y}^-_b, \textbf{X}_b^-\) in this course) will serve as a test dataset for that particular bootstrap sample.

We compute the OOB error as the difference of the out-of-bag observations \(\textbf{Y}^-_b\) and out-of-bag predictions \(\hat{f}_b(\textbf{X}_b^-)\).

The OOB error provides an internal estimate of prediction accuracy without needing a separate validation set.

Hence, random subsampling enhances the efficiency of bagging and supports model evaluation.

This is like inserting a Train-and-Test Validation inside the bagging algorithm.

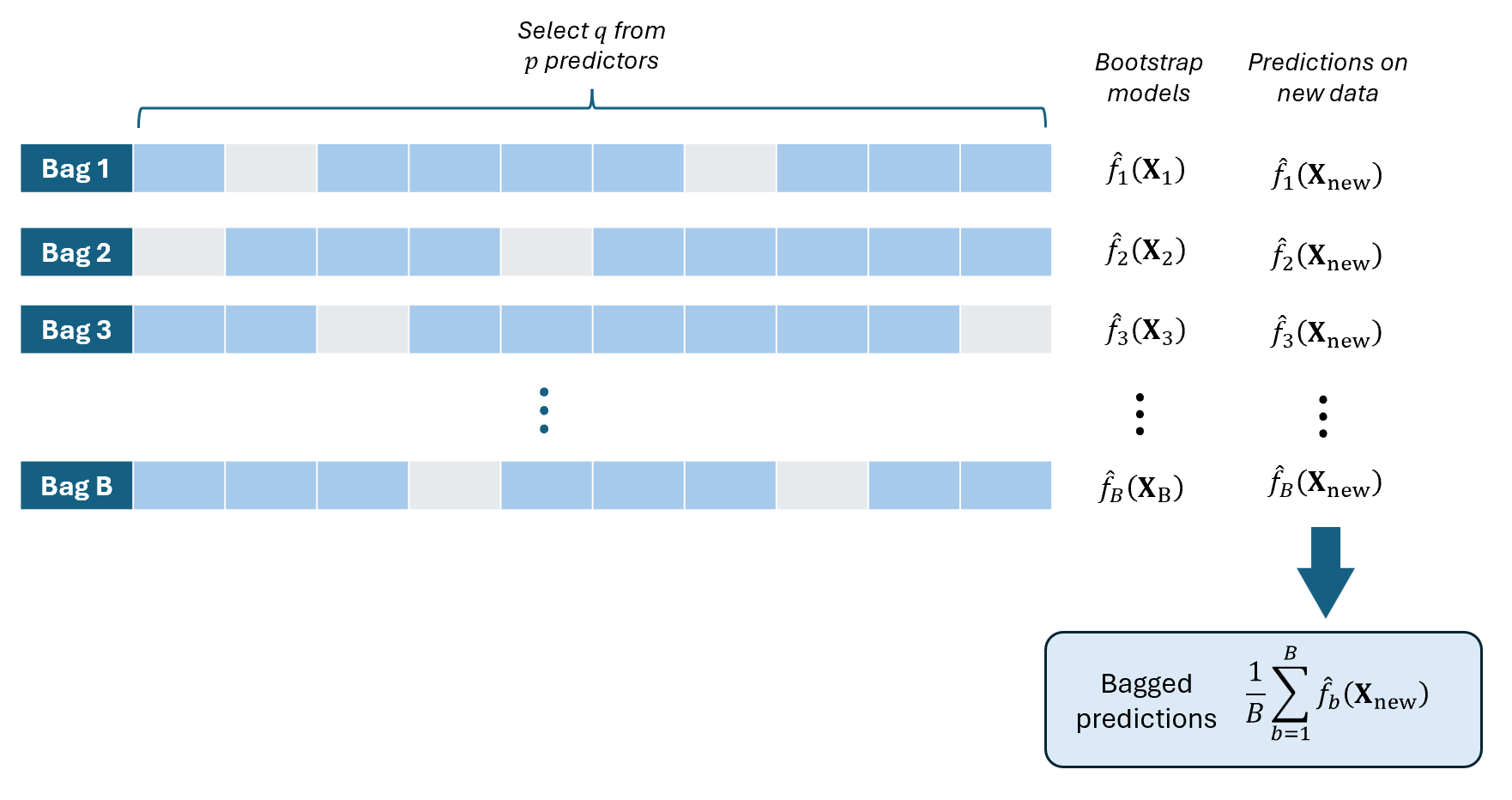

Random Permutations of Predictors

While Bagging focuses on resampling data, we can introduce additional randomness by randomly selecting or permuting predictors when training each model.

In this approach, you create many models where some models in the ensemble do not contain some predictors. This creates diversity among the models and enhances ensemble performance.

It appeals to relationships where the set of significant predictors vary across different “groups” or “types” of observation.

Bagging with Random Permutations of Predictors

Inputs:

- The training dataset \((\textbf{y},\textbf{X})\)

- Set of \(p\) predictors \(\{X_1, X_2, …, X_p\}\)

- Number of bootstrap samples \(B\)

- Number of predictors to sample per model, \(q < p\)

- New (unseen) data that contains values of \(\textbf{X}_{new}\) and we want predictions of \(\textbf{y}\).

Outputs:

- The “bagged” predicted value \(\hat{\textbf{y}}_{bag}\) of the new dataset \(\textbf{X}_{new}\)

FOR \(b\) in \(1\) to \(B\) DO:

Randomly select \(q\) predictors from \(X_1,...,X_p\).

Fit a model \(\hat{f}_b(\textbf{X})\) using only the selected \(q\) predictors.

Predict the value of \(\textbf{y}_{new}\) using the new data \(\textbf{X}_{new}\) by plugging in to the fitted model: \(\hat{\textbf{y}}_{b,new}=\hat{f}_b(\textbf{X}_{new})\)

END LOOP

COMPUTE “Bagged” predicted value on the new dataset as the average of the predicted values: \(\widehat{\textbf{y}}_{bag}=\frac{1}{B}\sum_{b=1}^B\hat{\textbf{y}}_{b,new}\)

This is especially useful if the number of predictors in your dataset is very high compared to the number of observations (\(p>>n\)). In each bootstrap model, use \(q\leq n\).

Variable Importance Measures

As we have discussed, bagging may improve the prediction accuracy, but the resulting model may be difficult to interpret.

This last method combines the random permutations approach with bagging with OOB error estimation to allow us to evaluate the impact of a variable in the bagged predictive model for a new angle of interpretability.

To compute this, each bootstrap model should be obtained from bootstrap sample \(m<n\) as well, and the OOB prediction error from the test dataset containing \(n-m\) observations must be obtained.

The impact score is usually computed as the difference of the OOB prediction error of models that include the variable from those that do not include the variable.

\[ \text{Impact Score of Variable } X_j = \\mean(\text{Error of Models without } X_j)- mean(\text{Error of Models with } X_j) \]

High impact score implies that the model will perform poorly if the variable \(X_j\) is removed from the model.

Suggestions for Research using Bagging

explore bagging algorithm for a real predictive modeling task. (e.g. improve a linear model via bagging)

bagging algorithm for modeling high dimensional data (i.e. p >> n). Hence, only a subset of variables can be considered at a time.

design a strategic randomization method and/or aggregation strategy for Bagging a certain model.

explore the impact score as a tool for variable selection.

References

Outline and content of this chapter are derived from handouts of Asst. Prof. Supranes of UP School of Statistics.

Modifications in bagging are from An Introduction to Statistical Learning by James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2013a). Refer to this book if you want to explore decision trees as well.