2.1 Prudential Rules

Macroprudential overlays were introduced alongside APG 223 to address specific lending excesses. These were:

2014 The first policy, announced late 2014, required banks to limit their lending to housing investors, or in other words, ‘buy-to-let’ borrowers that will rent out the housing Garvin et al. RBA - Macroprudential Limits on Mortgage Products: The Australian Experience (July 2021).

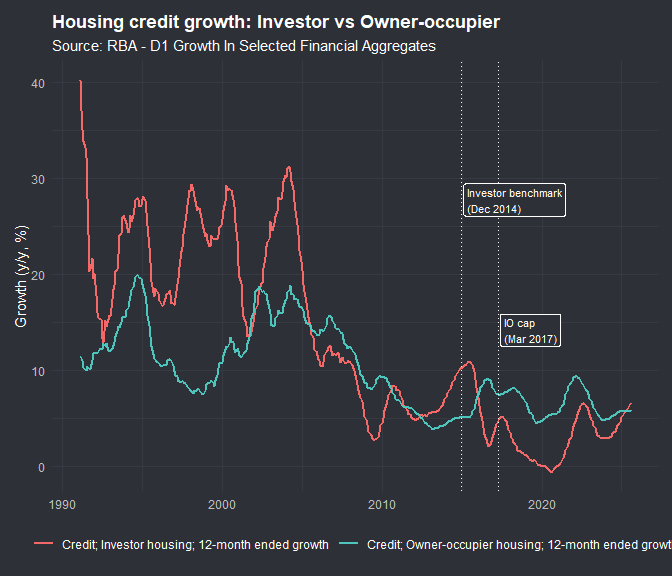

APRA asked banks to limit year-ended growth in investor housing credit to 10 per cent. Initially framed as a risk benchmark—not a binding cap—the measure nonetheless gained force over time: by mid‑2015, APRA had actively engaged banks to meet that benchmark, and by August 2015, Australia’s four largest banks were reportedly treating it as a de facto hard limit Garvin et al. RBA - Macroprudential Limits on Mortgage Products: The Australian Experience (July 2021).

2017 Following on from 2014 growth measures limits were imposed on interest-only (IO) mortgages, in which the loan principal stays constant and only interest is repaid. - A 30 per cent cap on new interest‑only (IO) lending as a proportion of new housing credit. This lending was deemed as procyclical and therefore a risk.

The RBA clarifies that APRA’s policies were product-specific, unlike most macroprudential regimes globally that typically target loans above high loan-to-valuation (LVR) or loan-to-income (LTI) ratios. APRA did advise banks to manage high-LVR and high-LTI mortgages, but quantitatively limited only investor and IO loans. The paper explains this approach was calibrated to avoid unintended impacts—for example, first-home buyers being disproportionately affected by a broad high-LVR cap—and because the elevated systemic risks were concentrated in speculative and IO borrowing. LTIs in Ireland were at 3.5 (with exception) for years, moving to 4x more recently. In my experience this often became a target for buyers.

In the Euro Area, macroprudential responsibility is shared between national authorities and the ECB. National authorities—often the national central bank, but not always—set and operate many tools (notably borrower-based measures such as LTV/LTI), while the ECB can apply more stringent capital-based measures under Article 5 of the SSM Regulation. Coordination and information-sharing occur continuously through the Macroprudential Forum and the ESRB framework. In Australia, prudential oversight of mortgage underwriting sits federally with APRA. The RBA contributes system-wide analysis and financial-stability advice and chairs the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR), but does not set underwriting rules; the CFR itself is non-statutory and has no direct policy powers. APRA’s Macroprudential Policy Framework makes clear that macroprudential tools are at APRA’s discretion (with CFR consultation), ensuring a single national standard rather than state-by-state variation. APRA Macroprudential Policy Framework

Empirical results from the RBA study confirm that these policy tools successfully and substantially curtailed growth in the targeted segments: targeted loan growth fell by 20 to 40 percentage points within a year of implementation. Large banks offset this by steering business toward non‑targeted products, while mid‑sized banks, lacking the capacity to substitute, saw sharper declines in overall mortgage growth. To see and measure the effects for myself I accessed data through the RBA.

In order to test whether APRA’s prudential interventions correspond to real shifts in credit growth, I applied two complementary statistical tools. The Chow test is useful when you have a clear policy date in mind and want to check if the data series shows a statistically significant change right then; I focused on investor versus owner-occupier growth because APRA’s measures were product-specific. The Bai–Perron method, on the other hand, looks across the entire series for any structural regimes that best explain the data; it is broader and less targeted. Using both lets me capture policy-timed changes while also checking that I am not over-fitting by seeing breaks everywhere.

Formal Chow tests indicate statistically significant breaks in investor housing credit growth at 2014-11 and 2017-03 (F-stats 13.3 and 21.1, p < 0.001). In contrast, no breaks are detected in the owner-occupier series (p ≈ 0.207 at 2014; p ≈ 0.367 at 2017). Difference-series tests (Investor − OO) also confirm significant breaks at both policy dates (F-stats 8.5 and 16.2, both p < 0.001). A Bai–Perron multiple-breakpoint search, in contrast, preferred 0 breaks for investor and 0 for owner-occupier, suggesting that while targeted shifts are detectable at policy dates, no additional persistent regimes are supported by information criteria.

The interest-only lending was the second major APRA intervention in March 2017, and tracking its share in new approvals provides a direct measure of policy impact. APRA itself states that “since the introduction of the benchmark, the proportion of new interest-only lending has halved” showing that the measure achieved its goal of curbing higher-risk forms of lendingAPRA - December 2018.

2.1.1 Practical Guidance

With the market-level interventions contextualised, I now examine the practical guidance documents APRA issued to banks. These do not create new laws, but they codify supervisory expectations and effectively set the floor for prudent practice. APG 223, in its 2022 final form and its 2025 marked-up revision, is central to how institutions implement day-to-day underwriting standards.

- Prudential Practical Guidance - APG 223 Resdidetial Mortgage Lending (June 2022)

- APRA Prudential Practice Guide (June 2025)

- Risk Management

An ADI (Authorised Deposit-taking Institution) is any bank, credit union or building society licensed by APRA to take deposits. APG 223 makes clear that where residential mortgage lending forms a “material proportion of an ADI’s lending portfolio” (Final APG 223, 2022, p. 3), the Board must explicitly address this risk in its risk appetite and risk management strategy. While “material” is not defined as a fixed threshold, in practice it means housing credit dominates most Australian banks’ books (often >60% of loan exposures).

The guidance changed Board-level responsibilities: before APG 223, risk frameworks might have mentioned housing credit generally, but now Boards must document and monitor how serviceability, origination, valuation and hardship fit within their risk appetite statement (RAS). The 2025 mark-up makes this even clearer, requiring consistent serviceability policies across products and explicit Board oversight of exceptions.

- Serviceability Criteria & Buffers

Serviceability is the test of whether a borrower can meet repayments under stressed conditions. APG 223 instructs ADIs to maintain “consistent serviceability criteria across all mortgage products … ensuring the borrower retains a reasonable income buffer above expenses” (APG 223 Mark-up, 2025, p. 7).

Practically, this means that when assessing a potential borrower, you don’t test their capacity at the contract rate alone. Since October 2021, APRA has required a minimum 3 percentage point buffer above the loan rate (APRA media release, Oct 2021). For example, if a borrower applies at 6%, the assessment rate is 9%. This buffer exists to absorb repayment shock — a critical concern given many households rolled off fixed-rate loans in 2023–24 as documented in the April 2023 Financial Stability Review and subsequent updates. This bugger was 2% in Ireland, this made for interesting dynamic mid 2022 when rates climbed significantly to combat inflation. Rising for sub-zero to 4% in just over a year to combat inflation.

Industry commentary supports the importance of buffers. The Australian Banking Association has argued that buffers reduce systemic arrears risk, while the RBA has noted that serviceability assessments ensure resilience to interest rate increases (RBA FSR, Oct 2021). Compared to Europe, where national regulators often apply loan-to-income or loan-to-value caps (ESRB, 2020), Australia’s approach is more focused on serviceability rate buffers than on absolute ratios.

- Origination Criteria & Verification

APG 223 frames prudent origination as starting with “sound loan origination criteria” (APG 223, 2022, p. 4). That means documented policies for: income verification, expense reasonableness, collateral, and overrides. Over time, this has evolved from reliance on the HEM benchmark (widely used pre-2018) to today’s expectation that lenders triangulate declared expenses, transaction data, and reasonable minimums.

Best practice now requires lenders to:

- Verify income with payslips or ATO notices of assessment.

- Adjust for volatility (e.g., bonuses, rental income etc).

- Scrutinise high-risk income types (casual, self-employed, or FIFO rosters).

- Maintain records of exceptions and rationale.

- Valuation, Hardship and Stress Testing

The serviceability buffer is a borrower-level stress assumption; stress testing refers to system-wide portfolio simulations (e.g., unemployment + property price fall scenarios). APG 223 expects ADIs to run “robust stress-testing frameworks” (2022, p. 12) that inform capital planning.

Valuation guidance is about property valuation, not abstract collateral. APRA expects ADIs to use independent, consistent valuation methods, with controls over AVMs (automated valuations) and panel valuers. This is crucial to avoid systemic over-valuation risks in mortgage portfolios.

On hardship, APG 223 sets expectations for fair, documented hardship treatment — loans in hardship must be separately identified, monitored, and provided for. Under s72 of the National Credit Code, a borrower can lodge a hardship notice (verbal or written) when they cannot meet obligations; the lender must consider a variation and respond within set timeframes. Typical outcomes include payment deferrals, reduced/paused repayments, temporary IO periods, or term extensions.

The Productivity Commission (2018) and ASIC (2019) highlighted risks around casual and contractor income verification, with APRA noting that prudent practice is to use averages and conservative assumptions for variable earners such as FIFO workers.